Researchers Study Retreating Glaciers using Thermal Drone Imagery

Rosie Bisset, a researcher at Edinburgh University, is mapping the surface of some of the highest glaciers in South America using data from drones equipped with thermal imaging cameras. Researchers have been monitoring the Andes glaciers with drones for several years, but Bisset is the first to conduct a thermal survey on her expedition.

Bisset is part of a research project called CASCADA, which brings together researchers from the UK and Peru to solve critical problems caused by retreating mountain glaciers. The glaciers of the Peruvian Andes have shrunk by about 30% in the last few decades, and pose a serious threat to the water supply of the people living in the Ancash region of Peru. Bisset is using thermal imaging data to understand how the surface cover of the glaciers is affecting the melt rate.

“One of the things that we’re particularly interested in looking at with the thermal camera,” Bisset explains, “is this material covering the surface of the glacier, which is called debris cover.” Debris cover influences the melt rate of the glacier in two ways, depending on the thickness: if there’s a thin layer of material covering the surface of the glacier, it enhances the melt rate by darkening the glacier surface and causing more sunlight to be absorbed. But a thicker layer of debris has the opposite effect, acting as insulation and preventing heat from reaching the surface of the ice.

“By measuring the surface temperature, you can model the thickness of the debris and how that’s likely to be influencing the melt rate.” Bisset used a drone fitted with a FLIR Vue Pro R 640 to measure the surface temperature of the glacier, and is currently building a mosaic of stitched-together thermal images to better understand its surface characteristics.

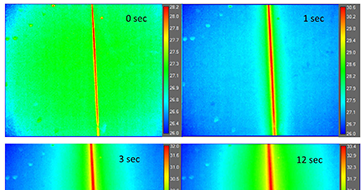

Thermal imagery collected with a FLIR Vue Pro R.

“It’s technology that’s developing quite rapidly at the moment,” Bisset says about thermal imaging. “It can tell us a lot of interesting things that we wouldn’t be able to look at with only visible imagery.”

Bisset had previously used thermal satellite data, but realized that drone imagery would provide her with much higher resolution and better data. Having no previous experience with drones, she took a crash course in drone operation to be able to complete the expedition. She worked with an Edinburgh-based company called Skytech Aerial that specializes in custom drone solutions to solve the challenges posed by flying a drone with a thermal camera (added weight) in high altitudes (thin air requires the propellers to spin faster).

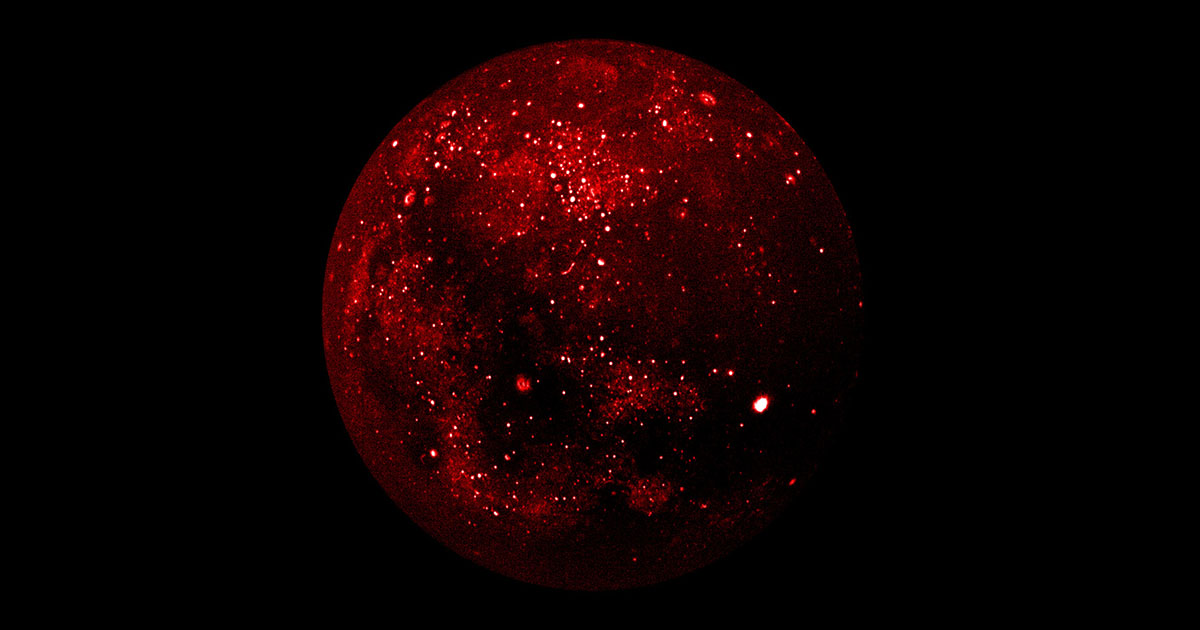

“Frank,” the drone used to collect data on the glaciers.

The trip to survey the glaciers took over 3 weeks, during which Bisset and her field assistant Callum Reay often hiked 700 to 800 meters a day at high altitudes, and camped in sub-zero conditions at night. Each carried a drone in their pack along with other survey equipment as they hiked up two glaciers, the Llaca Glacier and the Shallap Glacier.

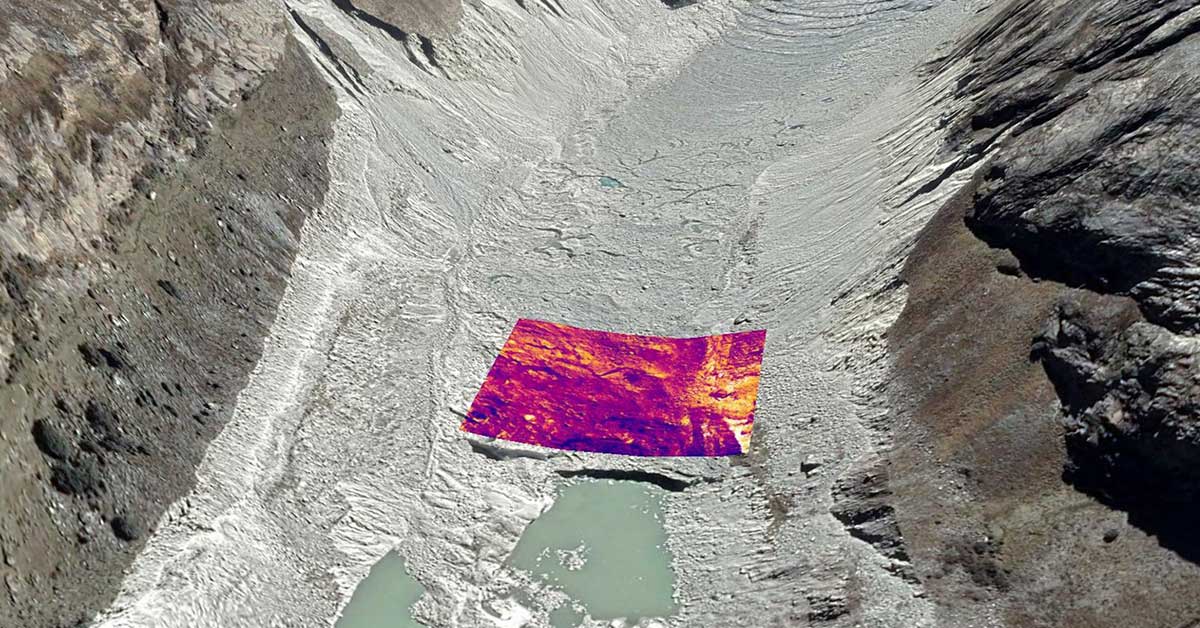

Survey area on the Llaca Glacier.

“It was a pretty equipment-intensive trip,” Bisset remarks, and there were several challenges when it came to collecting data. Though the drones reduced the amount of area the researchers had to cover on foot, they still had to go out on the glacier to put out “ground control” points where they would take additional temperature measurements to validate and calibrate the thermal data they collected by drone. The surface of the glaciers was often quite hazardous, with boulders rolling around, uneven surfaces, rockfalls, and large ponds of meltwater.

Thermal ground control point.

Back in Edinburgh, Bisset is working on bringing all her data together. “What we’re working on now is building a thermal mosaic and using that to model the debris thickness and other aspects of the glacier that might be impacting glacial melt rates. We’re also building a 3D model of the glacier that can be compared to previous 3D models of the glacier that were collected by a collaborator we’re working with.”

The collaborator, Oliver Wigmore, is a researcher at the University of Victoria Wellington in New Zealand. Since 2014, he’s visited the Llaca Glacier numerous times and collected 3D models of the surface with drones. Bisset will compare her 3D model to his data to see how the glacier surface is changing, and apply the new thermal imagery to gain a greater understanding of the debris cover and melt rate.

3D model of glacier surface.

The research that’s being done for the CASCADA project will feed into local policy making. There are two major impacts of glacial retreat in Peru: one is that as the glaciers are retreating, in the future there will be less water resources available for people in the region. There’s more than 250,000 people living directly downstream of the glaciers in the Ancash region of Peru, and shrinking glaciers will have a major impact on the timing and quantity of meltwater that’s available in the long term.

The other major impact is that as the glaciers retreat, they expose the naturally acidic rocks that are underneath the glacier. Runoff from these rocks then pollutes the hydrological system, making the meltwater dangerous for people to drink.

To address these challenges, local community groups are carrying out various projects, including wetland construction. The aim of the wetlands is to store water and release it more slowly, as the glaciers once did. Wetlands can also be populated with plant species that filter the heavy metals and other toxins from the water and make it safe to drink.

The research was primarily funded by the UK Natural Environmental Research Council (NERC) E3 Doctoral Training Partnership, with additional support from the Scottish Alliance for Geoscience, Environment and Society (SAGES). The research is also funded through a collaborative research programme between NERC and the Peruvian Council for Science, Technology and Technological Innovation (CONCYTEC).

Bisset, who is busy finishing her PhD, doesn’t know when she’ll be able to return to the Andes. But future researchers will definitely be back to monitor the glacial retreat and help develop solutions for the region.